- Home

- Fabio Fernandes

Solarpunk: Ecological and Fantastical Stories in a Sustainable World Page 4

Solarpunk: Ecological and Fantastical Stories in a Sustainable World Read online

Page 4

I started to walk faster, entered a bakery where the owner and the staff knew me and, without saying a word, asking for permission and apologizing by means of gestures and mimicry, ran to the back where there was a loading and unloading exit.

Outside, I walked in the opposite direction of my house until the first corner, and then I circled the block back, returning to the same stretch of sidewalk I had used when I left the office.

Then I saw the back of the gum-chewing guy a little farther on, standing at the entrance to the bakery, pretending to study the pastries in the display. He was obviously trying to find me in the middle of the confusion of customers jostling at the counter, balancing themselves on the poor little tables and making a noisy row at the cash register.

I had to admit that the chaotic interior of the establishment, the reflection of the sun in the window, the general smoke of fried bacon and water vapor that filled the bakery, all of this added to the fact that I was no longer there, made the task a bit hard.

I crossed the street and sat down on one of the small tables in a Japanese self-service restaurant that occupied part of the sidewalk, watching my poor stalker. He still stood, in a way that seemed pathetic to me, pretending to pay attention to the window for a few more minutes—trying to read omens and portents in the contours of the beaten egg cream and sugar covering the donuts, perhaps?—but then, with an attempt not at all happy to show dignity and indifference, he turned and walked away.

For a moment I was afraid he’d go straight to where I was, but instead he continued to walk in the general direction of my house. Interested, I followed him.

If my stalker really sucked in practice, at least someone had bothered to teach him the stakeout theory. Once you have lost sight of the person you should follow, the old masters say, it’s best to go to a place where the target will be forced to go sooner or later and, if possible, resume the job from there.

The alternative is to close shop for today and try again the next day, but my mysterious chewer wasn’t keen on doing tomorrow what he could do today. Following him I saw that he stopped very close to the building where I live, but at an angle that allowed me to observe the three broad steps of the main entrance without being picked up by the biometric camera of the electronic doorman. And he stood there, left shoulder barely resting on a light pole, waiting for me to appear.

I stood thirty feet behind him, and then I began to walk, fast and determined, in his direction.

I had a reasonable idea of what was going on. If I was wrong, however, what I intended to do with the imbecile would end up giving me a lawsuit for assault, maybe even bodily injury, if the D.A. had a migraine. But then I thought, so what? What’s one more wound for a leper, after all?

As soon as I saw myself two feet away from his back, I raised my arm and, without slowing down, grabbed him by the shoulder, twisting him violently around the pole. Before he had time to recover from the surprise and loss of balance, I punched him really good with a left hook.

The impact caused him to spit a milky, rosy mass on the post, and with my right hand I grabbed him tightly by the nape of his neck and pushed his head up to rub his nose, brow and cheeks in the ooze. When I let him go, he hesitated for a moment, and I wondered if he would sit down, but no: he stood. Hysterically, he rubbed his face clean with his shirt. But it was too late.

In the meantime, I’d stepped back and watched, knowing what to expect. It didn’t take long for the effects of the paste to manifest, as the saliva holding the virus inert evaporated: huge, grotesque and somewhat painful bubbles—judging by the moans and screams—began to erupt in his forehead and around his eyes. If any formed inside the nostrils, he would need medical help. If my mood improved, I might feel compelled to call someone.

The street wasn’t very busy and anyway people in my neighborhood know the value of giving ample space and privacy to their neighbor, especially when said neighbor seems to be of the violent kind and the victim is no one you know.

I felt a rather morbid satisfaction as I saw the face of my pursuer getting disfigured at high speed. Much of this satisfaction came from the fact that I had been right in my conjecture: what the imbecile had been chewing on was a “Punk’d,” a concoction made from a modified version of the papilloma virus, the same one that causes common warts. Punk’d is much faster, and creates much bigger and more fragile warts. It’s also non-contagious and its effects usually disappear in ten days tops.

This is not to say that an attack using this biological version of cream pie on the face isn’t humiliating, uncomfortable, and embarrassing to the victim, which is the whole point of the trick.

The product itself is illegal, but any anarchist with access to a backyard lab, any high school student with a penchant for bio-hacking is able to synthesize a few tens of milliliters in a few hours, like many snobbish It Girls, TV celebrities, police officers and even some especially photogenic senators have already discovered.

Noticing that he could still breathe, the stranger screamed in a soprano voice and ran.

“Tell Serapião I still owe him a kick in the ass!” I shouted at the fugitive, who was already turning the corner. Crying and gnashing my teeth. Bunch of jerks!

* * *

Antonio Kobaiashi de Toledo was a tall, thin man in navy blue trousers and a mustard-colored jacket full of pockets with buttons on his chest, sides, forearms, just as fashion dictated. His skin was dark like polished onyx. There wasn’t a single hair on his head above his ears, but beneath it he sported a long, bushy white beard.

The overall effect of this appearance, supplemented by a pair of round gold-rimmed spectacles, was that of an old person, conventional enough to be trustworthy, but endowed with deep wells of wisdom. Which must have been exactly the first impression Antonio wanted to plant in the unconscious of all those who came into his orbit.

He was already sitting at the counter when I arrived. There was a mug of amber-colored beer next to his elbow and a plate of olives in front of him. I introduced myself, asked for a mug for myself, and sat down. We began talking.

The first thing Antonio told me was that it was his call to the authorities that had led the police to break down Raul’s garage door.

“The guy hadn’t been coming to work for a week, he wasn’t even answering the phone. There had to be something wrong. Raul didn’t miss a day, even if he was working at home, investing his free time in some new project.

“Busting down the door struck me as a bit radical,” I pondered. “They had no employees or a virtual butler who could recognize the police credentials and open the garage?”

Antonio shook his head.

“The automation in the house was minimal, vestigial, even. The system washed and ironed the clothes, managed the water heating and vacuumed the floor, just that. His mother was virtually a Luddite, she didn’t trust machines to cook or wash the dishes. On top of that, Raul was paranoid regarding intelligent automation. He was afraid of being hacked, especially when he was taking important projects home.”

“And what project was that? If you can comment on it…”

He smiled.

“I don’t think I could, if I was officially involved, but since it was something between him and his girlfriend, Sabrina’s from the laboratory, I guess…”

That surprised me.

“Girlfriend?” I hadn’t told anyone that Sabrina, who claimed to be Raul’s fiancé, had hired me, but only that she was working for “interested parties” in the disappearance of his mother. And from what Sabrina’s friend, Cláudia, had said, their relationship was kept secret.

Antonio swallowed two olives and gave me a look of amusement and guilt, more or less like married men exchanging glances as they enter a whorehouse.

“I bet a little bird told you that the lovebirds’ courtship was highly classified, right?” He laughed. “Well, in a way, it was, but a bit clumsy. The rest of the engineering crew probably would have noticed if they’d bothered to pay attention. As fo

r me, how could I not notice? Raul had invited me to be the best man.”

“Best man,” I repeated, attesting my mental slowness.

“Best man. For the wedding. They hadn’t set a date yet, but they had decided on a kind of window of opportunity, an ideal period to tie the knot. They should have swapped vows a couple of months ago, but they gave up four months before that. When he told me my best man ‘services’ wouldn’t be necessary anymore, Raul was very embarrassed…”

“Did he give you a reason?”

“He just said that the right moment hadn’t come yet, something like that.”

“Did he mention his mother?”

Antonio paused for one moment.

“No,” he finally said. “I don’t think so. At least not in that context.”

I finished my mug and ordered another. While waiting, I commented:

“So he didn’t show for a week, and then you called the police.”

“Yes. I knew he was doing some informal testings off business hours, but as I explained, Raul was a straight arrow, and even if he was deep into some project at home, from midnight to 6 AM, he would never think of compensating overtime jumping out of normal business hours. He was dumb like that.”

My draft beer arrived and the high foam collar smudged the tip of my nose. I wiped the beer off it and asked him again about the project. Antonio replied pointing to my glass:

“This very beer you are drinking is made of yeast that turns the barley’s natural sugar into alcohol and releases carbon dioxide in the process.”

“Okay.”

“Much of the energy we use today in transportation, biodiesel, bio-kerosene, ethanol, is made in the same way. Yeast, or bacteria sometimes, turn biomass into precursor molecules that are then converted into the type of fuel that each specific vehicle requires. The old oil refineries turned into big breweries.”

“Because of global warming,” I suggested.

“Partly, yes. But the price of oil also had something to do with it.” The mischievous grin of the father caught in the brothel reappeared on his face. “Planting cane is still cheaper than drilling the continental shelf. But it won’t last forever. Because of the income.”

“Income?”

He paused to swap the empty mug for a full, then went on:

“Generally speaking, more energy is extracted from a liter of oil than from a kilo of cane. And the global demand only increases. Soon we will reach a point where it will again make sense, economic sense, at least to extract and refine oil, as it was done in the twentieth century. Unless we can extract more energy from plants.”

“Cellulose?”

“Cellulose, yes. Plants are made of things other than sugar, such as cellulose, fat, and protein, and there are biological pathways to convert all of those into fuel. The point is only about price and unwanted waste. Cellulose started to be a part of the scene in the beginning of the century. Animal fat has been used for decades to produce aviation kerosene. Protein is the new frontier, mainly because of waste.”

“Waste?”

“Ammonia. Nitrates. In the old days, people thought that this wouldn’t be a problem, that after yeast and bacteria finished turning the protein into fuel, the part with the nitrogen could be reused as fertilizer. A closed cycle: nitrates for soil, soil for plant, plant for nitrates. But then… Have you ever heard of nitrogen pollution?”

I shook my head. He swallowed three more olives.

“Bottom line, having loose nitrogen compounds in the soil, air, and water is not a good idea. Acid rain. Pollution of lakes and oceans. Bad, really bad. Not at first, but over time… Synthetic fertilizers had to be regulated almost to extinction some ten years ago. Hence, the golden dream of the protein biofuel was sent to the compost heap.”

“Unless someone invented a process that could neutralize nitrogen,” I added. “Which was what Raul and Sabrina were working on.”

“Yes, this. She developed the organism, he was working on the reactor, digester or whatever the type of device he had built at home. If it had worked out, it would have been fantastic.”

“Because the plants then would be fully exploited?”

“The animals too.”

In the kind of literature I usually read, the sentence “I felt an icy fist closing in around my heart” appears with a certain frequency, but I had never understood its meaning until that moment. Something was taking shape in the back of my mind and it was not good.

“Animals?”

“Of course.” The subject seemed to amuse my interlocutor. “Animals are fundamentally fat and protein. The fat processing is old stuff. In denser urban areas, restaurants can make good money by passing on leftover grease to mills. If you were to process the protein as well, it would be possible to reuse virtually all organic waste as a fuel source, the useless parts of animals slaughtered for consumption, carcasses of dogs and cats… In addition to creating a strong incentive for active pest control, such as rats and pigeons.”

“What about the bones?”

“Bone is also protein. Collagen, especially. We’d need filters to keep the minerals, calcium and everything else, but still…”

His eyes took on a distant, dreamy glow. It was the engineer’s brain, dwelling on speculation about an imaginary machine. I, on the other hand, could only think of the ending of a hundred-year-old movie, an old 2D production.

The protagonist, a famous actor of yore—not a good performer, but a fantastic screen presence all the same—ran down the streets shouting, “Soylent Green is people!”, referring to some green cookies that formed the basis of diet in his world. According to that plot, people were cannibals and did not know it.

“And why—” I forced myself, not without some effort, to put away my cinematic reverie. “—was he working on it at home?” The project would certainly be of interest to the company.

“It was something he was developing along with Sabrina. I believe it had begun as an official mission of the company, but it evolved into a pet project of the two. I think they wanted to present the technology to the board when it was ready, or at least when they already had a functional prototype. Or, well… Look, you didn’t hear that from me, but maybe they wanted to start a company. Their own company. If they could prove that all the development had been done outside office hours…”

“Got it.”

My stomach was upset. I couldn’t finish the second pint. An eloquent sign of declining health, in my case. After a few more lines of inconsequential dialogue, I excused myself and left.

On the way to the LRV station, hurriedly, I called my police contact. The voice exploded on the other side of the connection:

“Fuck, man, didn’t I tell you I had today off?”

Major Adriana of the Unified Metropolitan Police—my sweet little sister, born two years after me, always affectionate with her older brother.

“Shut that fucking filthy mouth of yours, Dri.” Whenever talking to Adriana, I always find it good to impose my authority right away. I can well imagine that anyone else trying to shut her up, including my brother-in-law, would end up with a nine-millimeter barrel stuck up in a nostril, or any other orifice. But being the big brother brings some atavistic privileges. “Shut up and listen to me. It’s important…”

She had said she wouldn’t have time to talk to me that day because of a party at my niece’s school, but the fact that Dri had answered the call with a loud “fuck” was a sign that, at least for now, she was alone and could speak freely.

But I knew that wasn’t going to last, so I quickly summed up the events of the day and the hypothesis that had come to me during the conversation with Antonio, who was still upsetting my stomach.

She listened to me with some exasperation at first, but, as the implications of each stage of the investigation became clear, she began to show a more pronounced interest. In the end, we engaged in a good talk about the case, and then I got a lot of the information I presented right at the beginning of this story.

As soon as we finished the conversation, I was already inside the train, and she promised to send me a team of experts to take a second look at Raul’s house. With special emphasis on the car, which had been left in the garage after the removal of the body, and in the part of the garden where the policemen had smelled beer.

* * *

To my disappointment, the Archimandrite Serapião was neither fat nor old. He didn’t even stink. The guy who came into my office the next afternoon was tall, thin, exuding a soft aroma of mahogany and citrus with a brief note of frankincense. He was dressed in a sleek chalkboard-gray suit with a jacket full of pockets (and epaulettes on his shoulders, something that anticipated the safari fashion of the next season), a Panama hat and, not to say that everything about him was beautiful and up-to-date, he had a curly goatee that looked like the tail of a dead sheep glued to his jaw with spit.

“Good afternoon, Your Reverence.” The soft voice of my secretary greeted the newcomer.

His expression, which never was really pleasant to begin with, crumpled completely. The sheep’s tail now looked like a storm cloud, ready to release lightning. As for me, I smiled the most beatific smile as I signaled for him to sit down.

“The system had a problem yesterday and hasn’t returned to normality yet,” I said, expressing a commiseration that, I hope, sounded as false as it really was. “She meant Reverend.”

He grunted something as he sat down and, once settled, said, “I was surprised by your phone call. After the abruptness with…”

“But you didn’t go, so nothing bad happened.”

“Didn’t I go?”

“Do as I suggested yesterday, before you disconnect the phone.”

The archimandrite became livid. With almost clinical interest, I watched as the blood drained from his face. He would have gotten up and out of the office at that very moment. He might have tried to attack me, had it not been for the orders he had received directly from the Archpriest Sérvio, with whom I had spoken the night before.

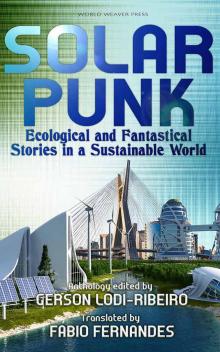

Solarpunk: Ecological and Fantastical Stories in a Sustainable World

Solarpunk: Ecological and Fantastical Stories in a Sustainable World