- Home

- Fabio Fernandes

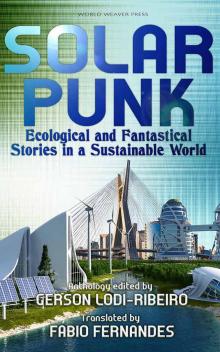

Solarpunk: Ecological and Fantastical Stories in a Sustainable World

Solarpunk: Ecological and Fantastical Stories in a Sustainable World Read online

Description

Imagine a sustainable world, run on clean and renewable energies that are less aggressive to the environment. Now imagine humanity under the impact of these changes. This is the premise Brazilian editor Gerson Lodi-Ribeiro proposed, and these authors took the challenge to envision hopeful futures and alternate histories. The stories in this anthology explore terrorism against green corporations, large space ships propelled by the pressure of solar radiation, the advent of photosynthetic humans, and how different society might be if we had switched to renewable energies much earlier in history. Originally published in Brazil and translated for the first time from the Portuguese by Fábio Fernandes, this anthology of optimistic science fiction features nine authors from Brazil and Portugal including Carlos Orsi, Telmo Marçal, Romeu Martins, Antonio Luiz M. Costa, Gabriel Cantareira, Daniel I. Dutra, André S. Silva, Roberta Spindler, and Gerson Lodi-Ribeiro.

SOLARPUNK: ECOLOGICAL AND FANTASTICAL STORIES IN A SUSTAINABLE WORLD

an anthology

Edited by Gerson Lodi-Ribeiro

Translated by Fábio Fernandes

World Weaver Press

Copyright Notice

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of World Weaver Press.

SOLARPUNK: ECOLOGICAL AND FANTASTICAL STORIES IN A SUSTAINABLE WORLD

Copyright © 2018 Fábio Fernandes

Originally published in Portuguese by Editora Draco © 2012

Interior illustrations © 2017 by José Baetas

All rights reserved.

Published by World Weaver Press, LLC

Albuquerque, New Mexico

www.WorldWeaverPress.com

Cover layout and design by Sarena Ulibarri

Cover images used under license from Shutterstock.com

First English edition: May 2018

Also available in paperback - ISBN-13: 978-0998702292

This anthology contains works of fiction; all characters and events are either fictitious or used fictitiously.

Please respect the rights of the authors and the hard work they’ve put into writing and editing the stories of this anthology: Do not copy. Do not distribute. Do not post or share online. If you like this book and want to share it with a friend, please consider buying an additional copy.

Preface

Sarena Ulibarri

The literary roots of solarpunk stretch back decades (at least), influenced and inspired by thought experiments such as Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed and Ernest Callenbach’s Ecotopia. One of the clearest forerunners is perhaps Kim Stanley Robinson’s Pacific Edge, the last of his “Three Californias Triptych.” The first of these three possible futures for California, The Wild Shore, envisions a post-apocalyptic world ravaged by nuclear war. The second, The Gold Coast, is a dystopian tale of rampant capitalism. To round them out, Robinson presents a third vision, Pacific Edge, a quasi-utopian future in which income inequality has largely been deflated and technology and architecture have adapted to create ecological harmony.

Though the Brazilian publisher Editora Draco was not directly influenced by Robinson’s triptych, the Solarpunk anthology had a similar genesis. First came Vaporpunk, an anthology of Victorian era alternate histories, showing a world run on steam power and clockwork. That was followed by Dieselpunk, alternate histories of the World Wars era, with the gritty aesthetic of gas-powered tanks and planes. When I asked editor Gerson Lodi-Ribeiro why he went with “Solarpunk” next, rather than some more established genre like cyberpunk, he told me, “after polluting Brazilian’s fantastic literature biosphere [with coal and then petroleum] it was the right time to write stories in self-sustaining fictional civilizations—no matter if those were located in future Earths or alternate history timelines—greener and more inspiring futures or timelimes not troubled by pollution, overpopulation, famine, mass extinctions and anthropogenic global warming. After all, as a reader, I was feeling rather bored myself with all those old dystopian plots.”

Weariness with dystopian plots, coupled with a growing awareness of climate change, has been a driving force in the renewed interest in ecological science fiction in the 2010s. The term “Solarpunk” was independently coined by about half a dozen different sources amidst a host of similar terms: ecopunk, hopepunk, brightpunk, eco-fabulism, eco-speculation, etc. While it is part of the larger movement of “climate fiction,” the “solar” in solarpunk has come to represent not only the ecological aspect of this budding subgenre, but also the idea of brightness and hope. Fascinating discussions have developed about what the genre is or isn’t, what it should look like, where it should stand politically, etc. Indeed, there is much more written about solarpunk than there is solarpunk fiction itself.

The limited cannon of self-proclaimed solarpunk fiction was one reason I thought it was so important for this anthology to be translated into English. When I negotiated the deal with Editora Draco, I didn’t know if the stories would even fit what was being defined as solarpunk in the English-speaking realm. But I knew it was essential that these early examples not be erased from the conversation simply because they were written in a different language.

The stories in this anthology are far less utopian and pastoral than much of the English-language solarpunk I’ve read. There is quite a lot of death and violence in them, and several of the stories show that just because a corporation or government is “green” doesn’t mean it’s free of corruption. And, no surprise when you understand the context in which they were published, two are alternate histories: “Xibalba Dreams of the West” envisions a high-tech Mayan and Tupi-descended society, untouched by European colonization, and “Once Upon a Time in a World” depicts a world in which the industrial revolution was replaced with a sustainable one, leading to accelerated technology and relative world peace—but certain familiar figures still want to make their grab for power. I was particularly surprised by the amount of gothic influence, most notably the immortal monster in “Cobalt Blue and the Enigma” and the overlap of science and religion in “Gary Johnson.”

All of these stories feature “sustainable” energy sources, but these energies aren’t always shown in a positive light. Because renewable energy has become so politicized in the United States, Americans tend to associate it with liberalism and left-wing ideology—the very idea of a world run primarily on renewables is often dismissed as idealistic and utopian. Brazil is actually one of the world’s leaders in renewable energy, with 76% of the country’s energy in 2017 coming from wind, solar, and hydropower. Brazil’s political landscape, however, is certainly not a liberal utopia. Far (very far) from it. Some of these stories reflect that dynamic and defy the notion that sustainable = utopian. The photosynthetic humans in “When Kingdoms Collide” are hiding a nefarious secret; “Soylent Green is People!“ shows how some scientists’ extracurricular experiments go very wrong; “Breaking News” covers a protest against a GMO greenhouse that takes a sinister turn; “Gary Johnson” is a Borgesian tale of an energy source that is just as unethical as it is abundant.

The two stories I think readers will most readily recognize as “solarpunk” are “Escape,” which is a race against time to prevent a planned disaster, and “Sun in the Heart,” a much more subtle tale about sacrifices and privilege in a world struggling with food shortages. But I hope you will read all o

f these stories generously and appreciate the rich and diverse worlds these writers have created. Many thanks to all of the Kickstarter backers who made this translation possible, as well as to the translator, Fábio Fernandes, who has been enthusiastic and diligent through this whole long process, and to the illustrator José Baetas, who has a brilliant eye for picking just the right scene to draw. Extra special thanks to Luca Albani for connecting me with Erick Sama and Gerson Lodi-Ribeiro at Editora Draco and therefore making this whole project possible.

And thanks to you, reader, for picking up this anthology, whatever it was that drew you to it. If you find these stories worthwhile, please tell a friend or leave a review. The world is connected through words, and yours matter just as much as anyone else’s.

Translator’s Note

Fábio Fernandes

It should come as no surprise the fact that the first solarpunk anthology came from Brazil. The biggest country in Latin America also has one of the highest levels of insolation in the world, at 4.25 to 6.5 sun hours/day. Not to mention the punk side of the equation: we strive to make a living in a shattered economy in every way we possibly can.

But let’s not forget that solarpunk wasn’t born in a vacuum. Most of the stories here will remind the readers of cyberpunk. There are echoes of Mirrorshades in this anthology, and that made my job as a translator even more challenging. As in the seminal cyberpunk antho, the solarpunk stories featured here are variegated: there is noir, alternate history, hi-tech utopias. There is ecology and there is punk. As in all good anthologies, the stories in it aren’t that easy to pin down or to pigeonhole—and that’s quite a feat of the original editor.

It was also a hard task for the translator; I’m used to translating from English to Portuguese, and that was particularly difficult to do in cases like Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange and Gibson’s Neuromancer, to name a few of the books I translated to Brazilian Portuguese along the years.

It was a pleasure to translate not only my fellow Brazilians, but also my friends. The challenge here was two-fold: I had to translate not only the stories, but also the author’s voices, so to speak. The Brazilian Portuguese colloquialisms and the very creative neologisms in virtually every one of these tales were a pleasure to read. I hope you feel the same.

Soylent Green is People!

Carlos Orsi

When the police finally knocked over the garage door and found Raul’s body inside the car, after the smoke subsided, everything pointed to a sad but reasonably simple case of suicide. It was only when the authorities began the always hard process of locating the victim’s next of kin to give them the news that the plot, as they say in crime novels, thickened.

Raul Gonçalves da Nóbrega was an engineer at DNArt & Tech. You certainly have some product of theirs in the bathroom, whether it’s a culture of bacteria to rub on the skin (DNArt holds the patent for an organism that uses UV rays for photosynthesis and secretes a golden pigment, acting as a sun block and suntan lotion at the same time), or the popular depilator-aphrodisiac hormone.

But I was talking about the next of kin. Raul was an only child, and even though he was over fifty years old, he still lived with his mother, a disabled lady of over ninety who, strangely, was not found in the house by the police officers who attended the incident. The house in which they lived had no employees, and residential automation was minimal and “dumb.”

Now, I suppose some eyebrows have risen when the word “disabled” appeared in the paragraph above.

In fact, it is hard to imagine a condition, short of death pure and simple, that can’t be greatly mitigated by some combination of gene therapy and cybernetics, and that these therapies are out of reach for a successful, single, childless engineer.

Besides, of course, ninety years is a long way from being a terminal age or something like that.

The reader probably already has the answer: Albertina Gonçalves was a member of the Church of the Puritans. Her faith allowed her to accept external aid to overcome physical weaknesses—glasses and wheelchair, for example—but no more direct interference in the Inviolable Temple of the Holy Spirit that was her body.

Not even the replacement of her opaque crystallines did she allow, preferring the milky semiblindness of the cataracts; medicine and supplements, from a certain degree of technological complexity, had to be discreetly “smuggled” into her food, which the son lovingly prepared and served, every day.

For months Albertina simply had not had lunch: she hoped Raul would come back from work so that he would make her a more substantial dinner and they could eat together, she in her bed, he sitting at the headboard.

The wheelchair (actually a maglev) was found in the room, floating beside the bed, but empty. There was a thin layer of dust on the seat, suggesting that it had not been used in ages. Her platinum-rimmed glasses, virtually useless because of the cataracts, but preserved as an icon of vanity, lay on a lavender piece of flannel on the bedside table. There were signs that someone had lain down and then got up—the bed was messed up, the cover pulled. There was a thin layer of dust on the sheets.

“Did she walk out there?” one of the two researchers there joked.

“Only if she was barefoot,” the other replied, pointing to the slippers under the bed.

The search of the house showed no sign of the old lady. The garage contained only the car. Inside the car, an off-road biodiesel-powered model, just Raul’s body. The wardrobes were full of Albertina’s clothes, with few empty hangers. If she had decided to travel, she had left with little more than the clothes on her body. There were also three suitcases, open and empty.

Other rooms of the property, which was small and functional but still managed to be luxurious, also revealed few clues. Raul’s room was in a better state than his mother’s: neat bedding, the sheet stretched out like that of a barrack cot.

The kitchen was just a kitchen, albeit on a large scale: built-in cupboards, a solitary glass in the center of the sink with an inch of juice in it, a huge fridge-cellar-freezer complex connected to a hybrid solar/wind system on the roof.

The stove, a thing of brushed steel and synthetic ivory, connected to a biodigestor tank in the service area, a cylinder the size of an adult Labrador dog where patented bacteria turned potato and banana peels plus used soybean oil into fuel.

The service area looked out onto a narrow, but long, lush garden, where, in the middle of walkways paved with aged pink marble, there were some empty cages and bird feeders that did not seem to attract a large audience. One of the policemen noted in his report that he smelled beer somewhere between mulberry trees and ornamental bromeliads, but the observation did not catch anyone’s attention.

* * *

That’s where I came in.

Like the faithful Puritans, in her will and testament Albertina had left all her possessions to the Church if Raul was not alive when she died. The combination of a relatively long life, closed after decades past at the expense of a wealthy relative, and compound interest, is powerful. Therefore, to establish that the mother was dead and her son had preceded her into the Great Mystery became a matter of the utmost interest to the supreme leader of the denomination, the Archpriest Sérvio, who quickly put the considerable legal machinery of the Church to work toward this end.

I suppose the Archpriest would not have had any excuses to hire me right away—I can imagine him listing the various precedents of unworthy men called to serve the Lord’s cause, such as disobedient Jonah, the adulterer David, or the cowardly Peter—but my agency certainly came into the case still well below the radar of his lawyers. Although my participation has ended up tied to the Church’s demand, the fact is that I entered the investigation via another source entirely.

Sabrina was a tall, long-haired brunette, with brown eyes and skin a color between light brown and deep red, the exact shade of my favorite brand of bitter ale. Her lips and nose were too thin for the fashion of the time; her nose, without being protruding, was narrow like a ra

zor, which gave her a cruel appearance that, honestly, did not bother me at all. I was sitting when she walked into the office in a short white dress. Her knees mesmerized me.

“Your secretary said I could come in.”

My silence had probably made her uncertain. I shook my head a little to get back on the ground, smiled and pointed to one of the two empty seats I reserved for clients.

“My secretary” was a mediocre system of commercial automation that basically scanned visitors for hidden weapons or incompatible biological material (some types of mouthwash don’t interact well with the bacteria I use to prevent oily skin, and dribbling splutters during the conversation is kind of boring), also making an anthropometric survey of the visitor in the social networks and in the Military Police and Federal Police files.

So, in the three seconds that Sabrina took to sit elegantly in the armchair, my desktop showed me her personal page on FaceSpace, her Currículo Lattes, and a “nothing” from the Public Security Bureau. To get a credit analysis I would need her Social Security number, which she would give me if I took her case, whatever it was.

According to “my secretary,” her name was Sabrina Toledo, 48 years old, half a dozen PhDs in areas such as medicine, genetics, organic chemistry, biophysics, and agrotechnology. She was an employee of DNArt & Tech’s R & D department.

“Dr. Toledo.” I leaned my elbows on the desk and steepled my hands right below my chin. “How can I help you?”

There was no more insecurity in her eyes, only a cold skepticism. I could almost see the glow of her brain cells firing as she tried to decide whether I was serious or a fraud, whether to tell me everything, or maybe just a little, or turn around and leave without opening her mouth.

“My husband.” For some reason, she decided I deserved a vote of confidence. “He’s dead.”

Solarpunk: Ecological and Fantastical Stories in a Sustainable World

Solarpunk: Ecological and Fantastical Stories in a Sustainable World